An Interview with

JOHN LASSETER

Part 3

By Lawrence French

LAWRENCE FRENCH: How do the ants finally defeat the grasshoppers?

JOHN LASSETER: In the end, the ants have had the ability to defeat the grasshoppers all along. Flik shows the other ants, by example, that the secret is to stand together, and to believe in themselves. Once they realize that, they can defeat the grasshoppers. One of the challenges we had was how to make this film be not so predictable. Because once you start the movie, you know what the ending is going to be. Hopper is the bad guy, and it's inherently quite predictable, so the challenge was to go through the story and work with it so you still have surprises, and keep the audience wondering what's going to happen next.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: How deeply do you analyze the story and characters??

JOHN LASSETER: We are constantly analyzing it on many different levels,

throughout the story development. Classic three act structure, character arcs, and so on.

We work months on that kind of thing, to find out how the characters fit into the story.

How they all tie together. It's a very laborious process, but it gives you the subtext you

need, because we are always interested in having things happening deep down in the characters

that you can feel. We want to get the right subtext.

JOHN LASSETER: We are constantly analyzing it on many different levels,

throughout the story development. Classic three act structure, character arcs, and so on.

We work months on that kind of thing, to find out how the characters fit into the story.

How they all tie together. It's a very laborious process, but it gives you the subtext you

need, because we are always interested in having things happening deep down in the characters

that you can feel. We want to get the right subtext.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: And you can use that in talking to the animators.

JOHN LASSETER: In talking to the animators, it's more in terms of acting, and character motivation. How the character may be saying one thing, but he's feeling something different. That's what gives the performances-in this case a bunch of insects-a reality, so that audiences can really feel for them, and understand what they're thinking and feeling.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: And you like to give each animator his own shots.

JOHN LASSETER: Yes, each animator had about three minutes in TOY STORY they could call their own. Not in sequence, but sprinkled throughout the movie, because there were so few animators, compared to a Disney film. We only had 27 animators, and on a Disney film they have over 70. One of the big focuses I have at Pixar, is I really want to make it a studio where people can get creative satisfaction, by making the movies they work on something they can be proud of. They can say, 'yes I'm proud to have worked on TOY STORY.' Also, it gives them the opportunity to have some creative ownership, so they can put their own input into the film. These movies are not made by one person alone, but by everyone working together. The goal at Pixar is not whose idea it was-that's not the important thing-the important thing is making the film the best we can. So we just keep building on each others ideas, and work, and keep polishing it, and out of that comes something much stronger, through collaboration.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: What kind of films did you look at to prepare for A BUG'S LIFE?

JOHN LASSETER: All kinds. It was a wide range of films that were all over

the map. From musicals, to action pictures, to unlikely hero pictures. Frank Capra pictures,

Buster Keaton. We did a lot of research, looking at Discovery channel specials on insects,

all sorts of things.

JOHN LASSETER: All kinds. It was a wide range of films that were all over

the map. From musicals, to action pictures, to unlikely hero pictures. Frank Capra pictures,

Buster Keaton. We did a lot of research, looking at Discovery channel specials on insects,

all sorts of things.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Andrew said you looked at movies like SPARTACUS and THE MUSIC MAN, but unlike most Disney animated films, this picture isn't going to have any songs in it.

JOHN LASSETER: That's right. We didn't set out and say, 'we're not going to make a musical,' but once we got into it, and the story evolved we looked at it we asked ourselves if it made sense to put songs in here, and we said, 'no, it makes more sense to have a big, epic film score.' We realized that this was a very epic tale, on the scale of LAWRENCE OF ARABIA or BEN-HUR. We call it an epic of miniature proportions. We are having a lot of fun with it from that standpoint, because it really is a spectacle like they did in the old bygone days of Hollywood. It has hundreds of ants in some shots, and they're not all doing the same action-there is a tremendous amount of acting within the crowd. Looking or running in different directions and acting in many different ways. That's one of the technical advances we've made. When we started out, in the budget we had about 50 crowd shots and we ended up doing 430 crowd shots. It's a huge number of epic shots, and the grandeur of the visuals. It's just a dry little island in the middle of a dry riverbed, but from an ant's point of view it's like the grand canyon. It's really huge, and exciting. Of course we also had to have some flying bugs, so we could have some neat flying scenes. The whole climax is a very exciting flying chase through a rainstorm. And rain to an insect is huge, it's what I like to call Volkswagens of water landing near you. Each raindrop is huge. That's something we really wanted, where they live goes through a dry season, and then comes the rainy season. It's kind of like California. Then, when the rain comes at the climax, it's spectacular. There's a gigantic intimidation sequence, when they finally stand up to the grasshoppers, and a number of exciting action set pieces occur throughout the movie.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Will it also be an epic length?

JOHN LASSETER: It's 88 minutes long, so it's significantly longer than TOY STORY. Randy Newman is doing the score, which is really epic, and it's in Cinemascope.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Did you think about using John Williams for the score?

JOHN LASSETER: We contemplated lots of people, but Randy Newman was our choice.

JOHN LASSETER: We contemplated lots of people, but Randy Newman was our choice.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: You were saying before, that when you started the film, you didn't even know if some of the shots were going to be doable.

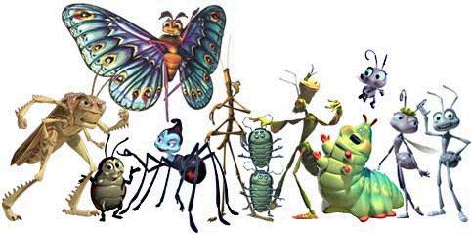

JOHN LASSETER: Yes, things like the crowd shots, and the caterpillar,

which was a very complex model-it had a very complex, organic shape to it-so we had to figure

out ways to do those things, as we were going along. The complexity of this film is so much

greater than TOY STORY. Even more so than the chase sequence in TOY STORY, which was the

most complex thing we did for that. When you look at scenes in A BUG'S LIFE, and you

realize that every blade of grass, every stone, and every leave was created and placed

there-it's mind boggling.. And there's so many of them. They blow in the breeze in a

natural way, they're organically shaped and don't ever feel like they were created by

a computer. Also, stylizing the backgrounds to have very attractive shapes, so it's

not exact nature, but inspired in many different ways. Buzz and Woody were some of the

most complex computer models ever created, and they were much more complex than any of

the other models in TOY STORY. And every single one of the characters in A BUG'S LIFE

is more complex than Buzz and Woody where. Just the number of characters in A BUG'S LIFE

is staggering. There's a bunch of miscellaneous bugs of all types. There's one scene

where Flik, finds the circus bugs in the city, but a city to an insect is a pile of trash

under a porch of an old beat-up trailer. To an insect that's like Manhattan. It's a

very fun sequence, and it's loaded with all types of bugs. The effects shots are astounding,

and it's just big, everywhere you look. In a BUG' S LIFE everything is natural, so

there's not a flat surface anywhere. In TOY STORY we were very lucky it was all a man

made world. In A BUG'S LIFE it's completely natural, so the ground is uneven, and it's

really complex to animate characters to move all over organic surfaces. We've redefined

the art form when it comes to texture maps and shading.

The lighting is spectacular,

The lighting is spectacular,

really artistic, and we set out thinking that for the final rendering we'd need about six

times the computer power we had on TOY STORY. It's ended up with double that, so now

we have twelve times the computer power of TOY STORY to do the final rendering. And still

there are frames of the film that are taking hundreds of hours of computer time a frame.

It's staggering! It's staggering how much time it takes to render these images. There are

forests of clovers, and grass is blowing in the breeze, and a huge tree is above them,

full of thousands of leaves, and we have shots with hundreds of ants, and it just keeps

multiplying out. Every shape and surface is organic, which takes up a tremendous amount

of computer memory, much more than a geometric shape would, which is mostly what we had

in TOY STORY. The scope of this film is huge, but it's great because it's all insects.

And we've really worked hard to keep reminding the audience that this is a tiny little

world they live in.

really artistic, and we set out thinking that for the final rendering we'd need about six

times the computer power we had on TOY STORY. It's ended up with double that, so now

we have twelve times the computer power of TOY STORY to do the final rendering. And still

there are frames of the film that are taking hundreds of hours of computer time a frame.

It's staggering! It's staggering how much time it takes to render these images. There are

forests of clovers, and grass is blowing in the breeze, and a huge tree is above them,

full of thousands of leaves, and we have shots with hundreds of ants, and it just keeps

multiplying out. Every shape and surface is organic, which takes up a tremendous amount

of computer memory, much more than a geometric shape would, which is mostly what we had

in TOY STORY. The scope of this film is huge, but it's great because it's all insects.

And we've really worked hard to keep reminding the audience that this is a tiny little

world they live in.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Did you ever have to scale back, because you find late in the game that something isn't actually doable?

JOHN LASSETER:

Oh, all the time. It's like, with this whole movie,

we bit off more than we could chew. But that's the history of Pixar. All our short films,

and TOY STORY were overly ambitious for their day. But when you get down to the core of

who we are at Pixar, we're constantly challenging ourselves. We don't want to keep doing

the same old thing. We'll never do the same old thing. The classic example is being told,

'here's a new computer that's ten times faster than the one you're using now. So that

means you can do the images and animation you were doing before, only ten times faster.

We get it, and do images that are ten times more complex, so it still takes us the same

amount of time. We're constantly pushing the outside of the envelope. In reality, when

we start any project we don't think of the technology, it's always the story and the

characters. The choice of subject matter, in the very beginning when we just have a

one sentence concept, is really based on the knowledge and love or our medium. Then,

we leave that behind and just worry about telling a great story, without handcuffing

ourselves technology wise. Then, at a certain point, we come in and think of the

technology we'll need to do the story. 'Where do we need to start researching?'

Because in ever story we do, there's something we've never done before. So we get

the technical directors, to start thinking about some of the things we don't know

how to do. Some of the things take a tremendous amount of time to research, but we

save some of those scenes to the end of the production schedule. So we're in

production for 2 ½ years, and in that time span, you can see the development of our

technology. In A BUG'S LIFE the first thing we did was the circus sequence, and then

the last things we're doing are incredibly complex, like the Times Square bug city shots.

You can see a growth in the complexity. The fundamental philosophy of how we work at

Pixar is: Art challenges technology and technology inspires art. So we come up with an

idea, and we challenge the technology to come up with a way to make it happen, along the

way. Then, the technology starts making images, something you've never seen before, and

that inspires you to say, 'let's do this.' So it's a constant openness, to be challenged

and inspired, so in the end you're doing things you've never seen before. That's why the

story is so important, because that's what I always revert back to. Something may look

great, but it wouldn't work for the story, so we can't do it. Sometimes there's some

painful choices that way. But most of times,

Oh, all the time. It's like, with this whole movie,

we bit off more than we could chew. But that's the history of Pixar. All our short films,

and TOY STORY were overly ambitious for their day. But when you get down to the core of

who we are at Pixar, we're constantly challenging ourselves. We don't want to keep doing

the same old thing. We'll never do the same old thing. The classic example is being told,

'here's a new computer that's ten times faster than the one you're using now. So that

means you can do the images and animation you were doing before, only ten times faster.

We get it, and do images that are ten times more complex, so it still takes us the same

amount of time. We're constantly pushing the outside of the envelope. In reality, when

we start any project we don't think of the technology, it's always the story and the

characters. The choice of subject matter, in the very beginning when we just have a

one sentence concept, is really based on the knowledge and love or our medium. Then,

we leave that behind and just worry about telling a great story, without handcuffing

ourselves technology wise. Then, at a certain point, we come in and think of the

technology we'll need to do the story. 'Where do we need to start researching?'

Because in ever story we do, there's something we've never done before. So we get

the technical directors, to start thinking about some of the things we don't know

how to do. Some of the things take a tremendous amount of time to research, but we

save some of those scenes to the end of the production schedule. So we're in

production for 2 ½ years, and in that time span, you can see the development of our

technology. In A BUG'S LIFE the first thing we did was the circus sequence, and then

the last things we're doing are incredibly complex, like the Times Square bug city shots.

You can see a growth in the complexity. The fundamental philosophy of how we work at

Pixar is: Art challenges technology and technology inspires art. So we come up with an

idea, and we challenge the technology to come up with a way to make it happen, along the

way. Then, the technology starts making images, something you've never seen before, and

that inspires you to say, 'let's do this.' So it's a constant openness, to be challenged

and inspired, so in the end you're doing things you've never seen before. That's why the

story is so important, because that's what I always revert back to. Something may look

great, but it wouldn't work for the story, so we can't do it. Sometimes there's some

painful choices that way. But most of times,

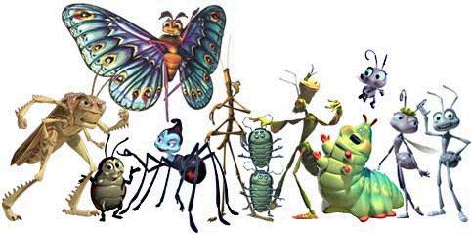

we see something amazing, and then evolve

the story. A case in point, on A BUG'S LIFE: we were doing a tree on the island where

the ants live. It's just one gnarly tree coming up out of the ground, and while they

were modeling it, we never had any intentions to use it the story, except for this one

knot hole where the ants hide this bird scarecrow they've built. But we started looking

around up in the tree, and it was beautiful. There were these branches everywhere, and

took our whole climax of the film and used the tree for it. Hopper gets loose, grabs

Flik, and flies away. The flying circus bugs take off after him, and we have this

exciting chase scene through the branches of the tree. It's lost all it's leaves, so

it's just branches and it's at night, in the middle of a big rainstorm, with thunder

and lightning, and the rain is splashing all around them. That's an example of the

art being inspired by the technology. It didn't change the story, but placed it in a

setting we would have never thought of. It was originally a storyboarded sequence of

them just flying, and when we saw the tree, we thought, let's put it there. There's

more things to dodge around and it's much more exciting that way.

we see something amazing, and then evolve

the story. A case in point, on A BUG'S LIFE: we were doing a tree on the island where

the ants live. It's just one gnarly tree coming up out of the ground, and while they

were modeling it, we never had any intentions to use it the story, except for this one

knot hole where the ants hide this bird scarecrow they've built. But we started looking

around up in the tree, and it was beautiful. There were these branches everywhere, and

took our whole climax of the film and used the tree for it. Hopper gets loose, grabs

Flik, and flies away. The flying circus bugs take off after him, and we have this

exciting chase scene through the branches of the tree. It's lost all it's leaves, so

it's just branches and it's at night, in the middle of a big rainstorm, with thunder

and lightning, and the rain is splashing all around them. That's an example of the

art being inspired by the technology. It didn't change the story, but placed it in a

setting we would have never thought of. It was originally a storyboarded sequence of

them just flying, and when we saw the tree, we thought, let's put it there. There's

more things to dodge around and it's much more exciting that way.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: How do you keep up your enthusiasm after four years on a project?

JOHN LASSETER: The thing is, because of the medium it's like building something from the ground up. It's like building a race car from scratch. Like digging in the earth to find the iron ore to build the engine. You don't know what it's going to look like until it's practically finished. That's how it is in film dailies, when the whole studio shows up and it's so fun, because it's like we're seeing everything for the first time, even though we've created the shots. To see it on film, certain shots just take your breath away. So I can say honestly, every day I see something I've never seen before. That completely inspires you, and keeps you inspired the entire way.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: There are no humans characters in the film?

JOHN LASSETER: No. They go near where humans live, but humans don't appear in the film.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Did shooting in Cinemascope present any problems?

JOHN LASSETER: Yes it did. Hold on, I'm getting another call. (Pause). That was Steve Jobs. You'll be glad to know I told him that since I was talking to you, I'd have to call him back later.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Speaking of Steve Jobs, how involved is he with Pixar these days?

JOHN LASSETER: He spends a lot of time at Apple, and about a day a

week at Pixar. He's not involved in the day to day production here, he's more of a CEO-a

kind of a global thinker, a long term thinker. But Steve's believed in us from the beginning.

JOHN LASSETER: He spends a lot of time at Apple, and about a day a

week at Pixar. He's not involved in the day to day production here, he's more of a CEO-a

kind of a global thinker, a long term thinker. But Steve's believed in us from the beginning.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: When Steve Jobs bought Pixar, he really took a big leap of faith, didn't he?

JOHN LASSETER: Yes, we were all working at Lucasfilm, and this supposed boy genius from Silicon valley, who just got fired from Apple, was coming up to take a look at us, to see if he was interesting in buying the computer division at Lucasfilm. At the time there were only forty of us, and Steve looked at us, but what impressed him was not the technology we were working with, but the people. So he ended up buying us, and continued to invest money, hoping that one day he'd get some sort of return on his investment. He waited over ten years, and supported us all that time, before we had a hit with TOY STORY. In today's business market, where everyone wants an immediate return on their investment, that's sort of amazing.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Have you talked to George Lucas, since he sold Pixar to Steve Jobs?

JOHN LASSETER: Oh sure. He's great. He's been over to visit us.

He's like a very proud father. We have a great relationship with his company. We have

a lot of friends at ILM, and use Skywalker sound exclusively for all of our soundwork.

Gary Rydstrom has done the sound for all of our short films, and all of our movies.

We wouldn't go anywhere else. Gary is really excited about doing A BUG'S LIFE, and

he's coming up with some great stuff for us. He's amazing. When I was at Skywalker

Ranch

for the final mix of TOY STORY, with Gary Rydstrom and Gary Summers, we were

waiting for reels to be changed and we were lamenting the fact that all these sound

system trailers are so LOUD. They hurt your ear, they're stupid and lame, and Gary

Summers was saying he had been talking to the THX people, and said, "you should do

something that's different and funny, and not quite so assaultive, and then the next

thing you know we started bouncing ideas around, and the next day we had lunch with

the THX people, and they loved the idea we had, so right after we did TOY STORY, we

animated this little short for a THX trailer, with TEX, the little robot. Gary

Rydstrom and Gary Summers did the sound for it. People just love it. It's become

very successful for them. My whole philosophy was to do it with humor and do it

with a character, because I'm a firm believer that people really tune into characters

more. Then you could do more gags for the next one, and have it a running thing.

Every year or six months they could produce another one, and have this little 60 second

cartoon before the movie. There already talking about doing another one. They

showed it before the STAR WARS movies, when they were re-issued. I saw the STAR

WARS movies again over at Skywalker Ranch. My wife had never seen STAR WARS.

I told her I wouldn't have married her if I had known that. It's such a core to

my whole being, that movie, as it is to everyone I know who's in the industry.

So many people are doing what they're doing now because of that movie. They saw

it when they were nine or ten, and now they're in the film business. It changed

the whole film industry.

for the final mix of TOY STORY, with Gary Rydstrom and Gary Summers, we were

waiting for reels to be changed and we were lamenting the fact that all these sound

system trailers are so LOUD. They hurt your ear, they're stupid and lame, and Gary

Summers was saying he had been talking to the THX people, and said, "you should do

something that's different and funny, and not quite so assaultive, and then the next

thing you know we started bouncing ideas around, and the next day we had lunch with

the THX people, and they loved the idea we had, so right after we did TOY STORY, we

animated this little short for a THX trailer, with TEX, the little robot. Gary

Rydstrom and Gary Summers did the sound for it. People just love it. It's become

very successful for them. My whole philosophy was to do it with humor and do it

with a character, because I'm a firm believer that people really tune into characters

more. Then you could do more gags for the next one, and have it a running thing.

Every year or six months they could produce another one, and have this little 60 second

cartoon before the movie. There already talking about doing another one. They

showed it before the STAR WARS movies, when they were re-issued. I saw the STAR

WARS movies again over at Skywalker Ranch. My wife had never seen STAR WARS.

I told her I wouldn't have married her if I had known that. It's such a core to

my whole being, that movie, as it is to everyone I know who's in the industry.

So many people are doing what they're doing now because of that movie. They saw

it when they were nine or ten, and now they're in the film business. It changed

the whole film industry.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: What are some of the cartoons that influenced you?

JOHN LASSETER: The number one influence was the Chuck Jones Warner Bros. cartoons. Also the Disney animated films, and JOHNNY QUEST. I was a big JOHNNY QUEST nut when I was a kid. Most recently the Japanese director Hayao Miyazaki, who did MY NEIGHBOR TOTORO. That's his best known film that been released in this country. His greatest film though, is probably LAPUTA, CASTLE IN THE SKY. It's a remarkable work. He's been a huge influence in my later years, and he's actually become a friend of mine. I met him when I was in Japan for TOY STORY.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: What about Live action directors?

JOHN LASSETER: Frank Capra is a tremendous influence on me,

because of the heart in all of his films. Of all the live-action directors, Capra is

probably the one I admire the most. And Preston Sturges, with his rapid fire comedy.

I love Howard Hawks stuff, like HIS GIRL FRIDAY. That's one of my favorites, and RED

RIVER. Of the later directors, Spielberg and Lucas, of course. I also love Buster

Keaton. He's like the human animated cartoon.

because of the heart in all of his films. Of all the live-action directors, Capra is

probably the one I admire the most. And Preston Sturges, with his rapid fire comedy.

I love Howard Hawks stuff, like HIS GIRL FRIDAY. That's one of my favorites, and RED

RIVER. Of the later directors, Spielberg and Lucas, of course. I also love Buster

Keaton. He's like the human animated cartoon.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Like Howard Hawks, you use a very fast pace, and overlapping dialogue. TOY STORY is quite dense with information.

JOHN LASSETER: Frank Capra talks about that in his autobiography, about how he would try to get actors to do something, then rehearse it, and say, "now that you know what you need to do, make it as fast as you possibly can." And he would often end up using those takes. On film, and especially in animation, when you're just using the voice of a character, things slow down dramatically. In just a normal conversation, if you just take the audio and animate to it, it would be very slow. So that's something I remembered and use in my own direction. I try to speed things up, it sort of keeps things alive, especially when dealing with comedy.

LAWRENCE FRENCH: Did you use your kids as an instant test s creening audience for the movies while your making them?

JOHN LASSETER: Yes, absolutely. I have five boys, from ages

2 to 18. I

would show them TOY STORY in all the different stages, and it was very

important to see their reactions, because I not only wanted to judge the reactions

for little kids, (to see if I was making them too scared), but also on my teenager,

because it was important for me to make it work for teenager's as well. I wanted

TOY STORY to appeal to teenagers and make it something that they would think

was cool to go see. They always say teenage boys are the toughest audience

you can get.

would show them TOY STORY in all the different stages, and it was very

important to see their reactions, because I not only wanted to judge the reactions

for little kids, (to see if I was making them too scared), but also on my teenager,

because it was important for me to make it work for teenager's as well. I wanted

TOY STORY to appeal to teenagers and make it something that they would think

was cool to go see. They always say teenage boys are the toughest audience

you can get.

This concludes the John Lasseter Interview

Thank-you to Lawrence French for providing it